FAQs about Government Shutdowns

Updated July 21, 2023

Author: Catherine Rowland, Legislative Affairs Director (catherine@progressivecaucuscenter.org)

1. Why does the government shut down?

The government shuts down when Congress fails to pass legislation known as “appropriations” bills, which fund federal agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and programs like the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Appropriations bills typically fund the government through the end of each fiscal year (September 30). If a new appropriations bill has not been signed into law by that expiration date, Congress must pass a stopgap measure known as a “continuing resolution” (CR) to fund the government at current spending levels. For example, if a CR were to pass this year, it would fund the government at Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 levels. Without a new appropriations bill or a CR, the government shuts down.

2. Which government services and programs change during a shutdown and what impact does that have on the public?

The extent to which a shutdown impacts federal programs and services varies. Congress has occasionally passed some of the 12 appropriations bills, allowing agencies and programs that those bills fund to remain functional while others shut down. This is called a “partial” government shutdown. However, if Congress does not pass any appropriations bills, all government functions halt with limited exceptions (see question 3 for a list of exceptions).

Even a partial government shutdown has real human impacts. Below are numerous examples from the partial government shutdown between December 22, 2018, and January 25, 2019 (herein, the 2018-2019 shutdown):

The Food and Drug Administration paused routine inspections, which endangered the public by allowing unsafe food or medical facilities to operate undetected. In the shutdown’s first weeks alone, the agency canceled more than 50 “high-risk” inspections, which typically involve food considered vulnerable to contamination like seafood, cheese, and vegetables.

More than 86,000 immigration court hearings were canceled, delaying immigration proceedings for people who may have been waiting for their day in court for years and worsening an already substantial case backlog.

The National Park Service stopped trash collection and road repairs, which allowed unsanitary conditions to fester and dangerous roads to remain in use, thus risking public safety. Some parks closed entirely, as did the Smithsonian museums, the National Zoo, and the National Gallery of Art, disrupting families’ travel plans and costing the government revenue it would otherwise collect from fees and souvenir and concession sales.

In some states, the shutdown jeopardized cash assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. The National Governors Association warned Congress nearly one month into the shutdown that although states had covered TANF costs up until that point, “states’ abilities to continue covering these costs may change based on caseload and enrollment. Payments to both individuals and families, in addition to support services funded by TANF, are at risk unless funding is restored.” Had the shutdown been longer, low-income families and children could have lost their cash assistance, pushing families further into poverty and taking away assistance that helps children’s short and long-term development.

3. Which government services and programs don’t change during a shutdown?

Again, the exact services and programs a shutdown affects depend on whether the shutdown is total or partial. During a partial shutdown, some government agencies remain operational and continue providing services to the public.

Certain government functions continue regardless of whether the agencies responsible for them shut down. A 1981 memo from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) referred to these activities as those related to “national security or the safety of life and property.” Activities that fall under this category include:

inpatient hospital care and emergency outpatient medical care

air traffic control

law enforcement

border security

disaster aid

power grid maintenance

However, these activities may still experience disruptions. For example, during the 2018-2019 shutdown, air traffic controllers were forced to work without pay and began calling in sick in large numbers in protest. The resulting shortages caused major flight delays, and on January 25, 2019, New York’s La Guardia airport was closed to incoming planes entirely.

Government activities that are not funded by annual appropriations bills also continue during a shutdown. This includes the U.S. Postal Service, which sustains its own operations through stamp sales, shipping costs, and more. This also includes permanently-funded programs, like Social Security and Medicare. Again, however, a shutdown may cause disruptions even as services continue. For example, during the FY 1996 shutdowns, although Social Security benefits remained funded, most Social Security Administration (SSA) staff were initially furloughed because appropriations from Congress fund their salaries. As a result, the agency did not have enough staff to respond to public inquiries or process address changes and new benefit claims. While SSA called back staff to fulfill these functions, the incident illustrates that even programs not subject to appropriations can suffer during a shutdown, forcing the public to grapple with issues like delayed benefits.

4. What happens to federal government workers during a shutdown?

Federal employees who work at an agency that has been shut down are either furloughed—that is, prohibited from reporting to work and are not paid—or must work without pay if they are considered essential to fulfilling ongoing government functions, like those required to maintain public safety. Historically, Congress has passed legislation to pay both categories of employees retroactively once the government reopens. However, this backpay does not alleviate hardships federal employees experience during a shutdown. During the 2018-2019 shutdown, an estimated 2 million people worked for the federal government. Approximately 380,000 were furloughed, while 420,000 were forced to work without pay. As a result, one study showed, many of these workers delayed their monthly mortgage or credit card payments, putting them at risk of late fees or defaulting on their loans. Even more workers were furloughed during the 2013 shutdown, during which more than 2 million people worked for the federal government and approximately 850,000 were furloughed.

Unlike workers the federal government employs directly, government contractors forced to stop working do not typically receive backpay following government shutdowns. During the 2018-2019 shutdown, an estimated 4.1 million people worked under government contracts, though the precise number furloughed is unknown. As in federal employees’ cases, the burdens shutdowns impose on government contractors may have long-term consequences for workers’ financial futures. NPR published the following account from a government contractor during the 2018-2019 shutdown:

“The shutdown has already upended Joe Pinnetti’s plans for finishing his bachelor’s degree in information technology while working days as an IT contractor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in western Massachusetts. Pinnetti has been unable to perform his $22-an-hour job since the shutdown began. “It’s going to be rough — I’m digging deep into my savings right now,” says Pinnetti. “The problem is I’m already having to sacrifice things to do so: I might have to take a semester off from school to rebuild my savings.””

5. What does a government shutdown cost?

Shutdowns hurt the public, who must grapple with disruptions to federal services and programs, and federal employees who are furloughed or forced to work without pay (for additional details, see questions 2-4). Shutdowns also impose a substantial burden on the government. Both OMB and federal agencies must create and coordinate shutdown plans to inform federal workers of their status and ensure government functions essential to public safety and national security continue. This requires extra staff time and resources that could otherwise be spent addressing the public’s needs. Additionally, shutdowns cost the government revenue. For example, when national parks shut down, they cannot collect visitor fees or revenue from gift stores or concessions.

Shutdowns also hurt the economy. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the 2018-2019 shutdown cost the U.S. economy $11 billion—largely the result of federal workers cutting spending to cope with the loss of their paychecks. Workers’ stories indicated they would not necessarily resume spending after receiving back pay. The New York Times reported this example following the shutdown’s conclusion:

“Mr. Stevens said he had about two months of salary in savings when the government shut down, and his landlord helped out by postponing a rent payment. Even so, he said he had a pile of bills to tackle as soon as he got paid. Going forward, Mr. Stevens said he intended to sock away six months of salary. “No more fast food,” said Mr. Stevens, who lives in suburban Maryland. “Less entertainment. No more taking the kids out everywhere.””

6. How long does a government shutdown last?

Shutdowns’ lengths vary, as they last until Congress passes and the President signs appropriations bills to fund the government. The 2018-2019 shutdown was the longest government shutdown in U.S. history at 35 days.

7. How many times has the government shut down?

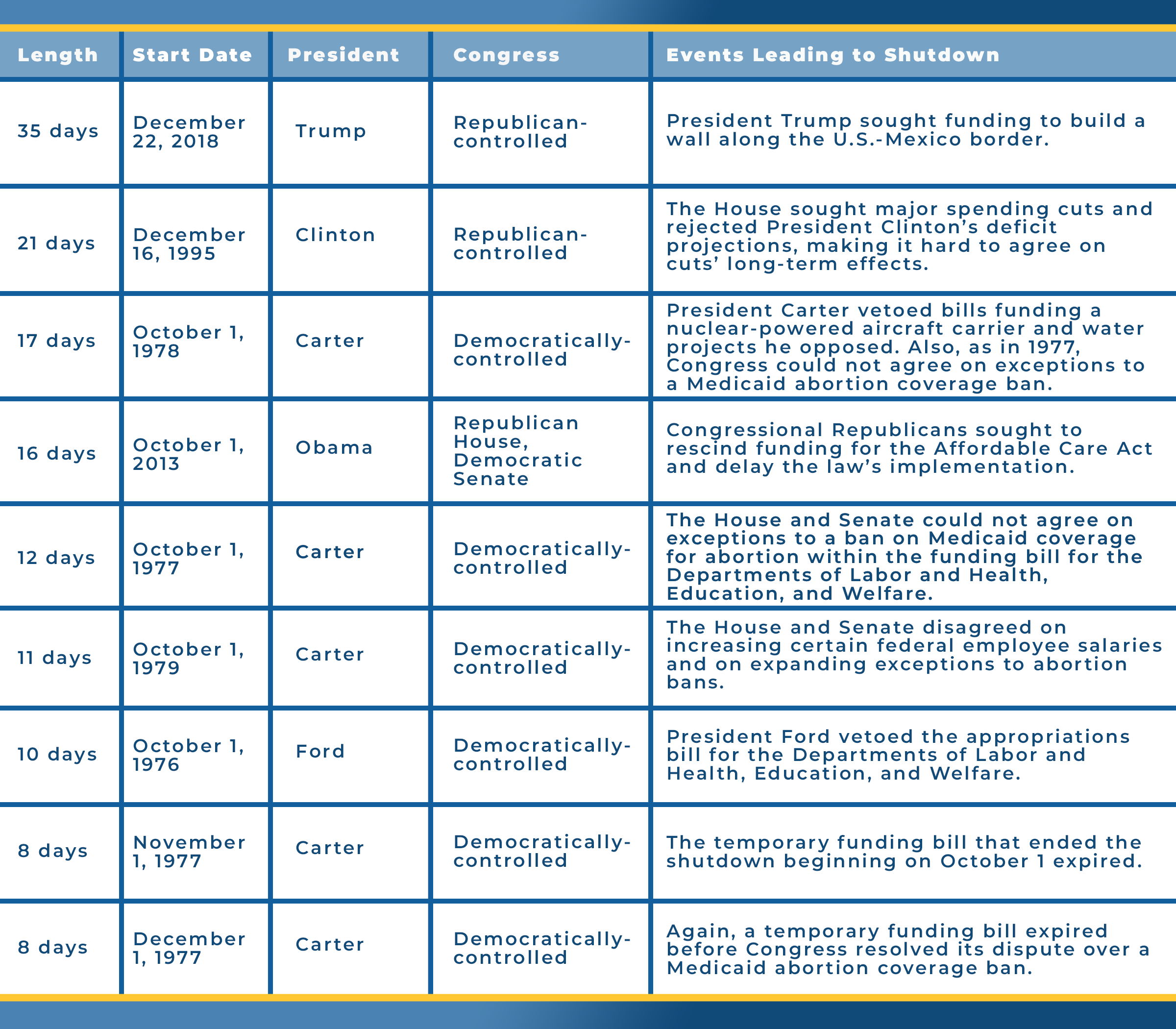

To date, the U.S. government has shut down 21 times. Of these, only nine have lasted more than one week. Below, in Table 1, is a brief summary of those nine shutdowns, in descending order by length.

TABLE 1: U.S. Government Shutdowns Lasting More Than One Week

Sources: Mihir Zaveri, Guilbert Gates, Karen Zraick. “The Government Shutdown Was the Longest Ever. Here’s the History.” New York Times. Jan. 25, 2019; Dylan Matthews. ”Here is every previous government shutdown, why they happened and how they ended.” Washington Post. Sept. 25, 2013; and Dylan Matthews. “All 20 previous government shutdowns, explained.” Vox. Jan. 12, 2019.

8. Why have government shutdowns been called “hostage situations”?

Because a shutdown is costly for the public, the government, and the economy, presidents and members of Congress have previously used the threat of a shutdown to extract concessions in spending bill negotiations. Like a hostage crisis, one branch might agree to the other’s demands, so they, in turn, “release” the hostage—meaning, agree to an appropriations bill and keep the government open.

For example, President Trump’s refusal to sign an appropriations bill that did not fund a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border led to the 2018-2019 shutdown. President Trump held government funding “hostage” in hopes that Congress would meet his “demand” and fund a border wall. Importantly, the actor holding the “hostage” must be willing to tolerate the harm a shutdown causes. In the case of the 2018-2019 shutdown, President Trump eventually agreed to sign an appropriations bill that did not meet his demand due to mounting pressure from lawmakers and the public in the wake of staff shortages among air traffic controllers and resultant flight delays. Thus, while a president or Congress can try to use government funding as a hostage to win their demands, they are not guaranteed success.

9. What has to happen to end a government shutdown once it starts?

Congress must pass and the President must sign appropriations bills to fund the departments and agencies that have shut down.

10. Can the President end a government shutdown unilaterally?

No, both Congress and the President must act to end a shutdown. Appropriations bills to fund the government advance in the same manner as any other bill: they must pass in both the House and Senate and the President must sign them into law.

11. When could a shutdown happen next and how does the recent debt ceiling deal affect this?

Current government funding expires after September 30, 2023. Without new funding bills or a CR, the government will shut down on October 1.

On June 3, 2023, President Biden signed legislation to suspend the debt ceiling until January 1, 2025. Lifting or suspending the debt ceiling does not increase federal spending—it merely adjusts the limit Congress places on the total debt the federal government can incur. Nonetheless, the threat of defaulting on U.S. debt has become a powerful political tool for lawmakers seeking spending cuts to federal programs and services. Indeed, the debt ceiling deal caps defense and non-defense spending for FY 2024 and 2025. The deal also reduces those caps by one percent if Congress puts a CR in place rather than pass new appropriations bills by January 1, 2024 and January 1, 2025, respectively. This threat of further cuts could serve as an added incentive for Congress and the White House to reach an agreement on appropriations bills before 2023 ends.