Manufactured Crisis: the debt limit in 2023

Last updated April 11, 2022

Author: Ricardo Pacheco, Senior Legislative Affairs Associate (ricardo@progressivecaucuscenter.org)

Introduction

For over 80 years, Congress has placed a cap on the total debt the federal government can take on, which is known as the “debt ceiling.” Since the debt ceiling’s genesis in 1939, Congress has altered that limit hundreds of times to ensure the United States does not “default” on—that is, fail to pay—its debts. A default would prompt a global economic crisis, the effects of which would be devastating for American families. Congress last raised the debt ceiling in December 2021 when, after lengthy negotiations, lawmakers raised the limit by $2.5 trillion to just under $31.4 trillion, where it currently sits.

The U.S. government reached its debt ceiling in January 2023, forcing the Treasury Department to use “extraordinary measures” to pay the government’s bills. It is unclear exactly when the government will exhaust those measures. While the Treasury Department has set a June 5, 2023 deadline for Congress to act or risk a default, the Congressional Budget Office expects the extraordinary measures to run out between July and September. What is clear, however, is that the government will inevitably hit the debt limit again soon, necessitating another increase or suspension to avoid default.

While Congress has always prevented a default, some deficit-hawk lawmakers have historically used the threat of one to extract concessions from their colleagues, usually at the expense of programs that help vulnerable communities. In 2011, for example, the standoff between then-President Barack Obama and the Republican-controlled House of Representatives over raising the debt limit ended in spending cuts to K-12 schools, rental assistance vouchers, environmental protection, and more. On top of that, the showdown resulted in the Budget Control Act of 2011, which placed budget limits on discretionary spending for the next ten years.

The 2011 debt ceiling showdown, in prompting draconian cuts, made it harder for federal programs to meet the public's needs. Nonetheless, on March 10, 2023, the House Freedom Caucus named some of their demands for lifting the debt limit, including rescinding President Joe Biden’s student debt relief plan and unspent COVID-19 relief funds, as well as repealing large portions of the Inflation Reduction Act., Given that such cuts are likely nonstarters for the Senate and White House, another debt ceiling clash looms on the horizon.

This explainer breaks down the debt ceiling’s history, its threats, and options for dealing with it—immediately and for good. Understanding these issues is important to avoiding harmful concessions that keep vital resources away from U.S. communities.

The Debt Limit’s Origins

Before 1917, Congress passed specific bills stipulating when and how the Treasury Department could borrow money and issue debt—a process even more cumbersome than the current one. Around the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917, Congress gave the Treasury more leeway, setting a topline limit on federal debt and loosening limits on specific debt issues. In 1939, Congress further simplified debt issuance by establishing one aggregate debt limit covering nearly all public debt. This framework remains in place today.

Under the 1939 framework, Congress allows the Treasury Department to manage the federal debt as long as total debt stays below a statutory debt limit that Congress sets. This statutory limit is what we know as the “debt ceiling.” Congress usually votes on that limit separately from the policies that necessitate issuing more federal debt. This allows Members of Congress to vote against “increasing the debt” while voting for record military spending and deficit-financed tax cuts for the wealthy. That means the debt ceiling does not prevent the government from enacting policies that increase U.S. debt.

The Threat of Default

Approaching the Debt Limit

Economists can predict roughly when the U.S. will exceed the debt limit. Nonetheless, Congress sometimes lets the Treasury hit the debt limit before voting to raise it. When the Treasury Department hits the statutory limit, it resorts to accounting schemes it refers to as “extraordinary measures” to finance the federal government’s obligations. These might include cashing in on existing government investments early. How long the Treasury can keep up these tactics depends on the daily inflow and outflow of spending and revenue, but typically the Treasury can buy Congress weeks or months to raise the ceiling.

On January 19, 2023, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen announced that the federal government reached the $31.4 trillion debt limit set in December 2021 and that the Treasury Department would use “extraordinary measures” to avoid a default. The extraordinary measures include redeeming existing and suspending new investments of the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund and the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund; suspending reinvestment of the Government Securities Investment Fund; suspending reinvestment of the Exchange Stabilization Fund; and suspending sales of State and Local Government Series Treasury securities.

What Would Happen if Congress Failed to Raise the Debt Limit?

If Congress failed to raise the debt limit before the Treasury Department exhausted its extraordinary measures, the federal government would default on its debt. This would prevent the Treasury from fulfilling the government’s financial obligations. The U.S. has never had a full-scale default since the statutory debt limit began, but Congress has come perilously close.

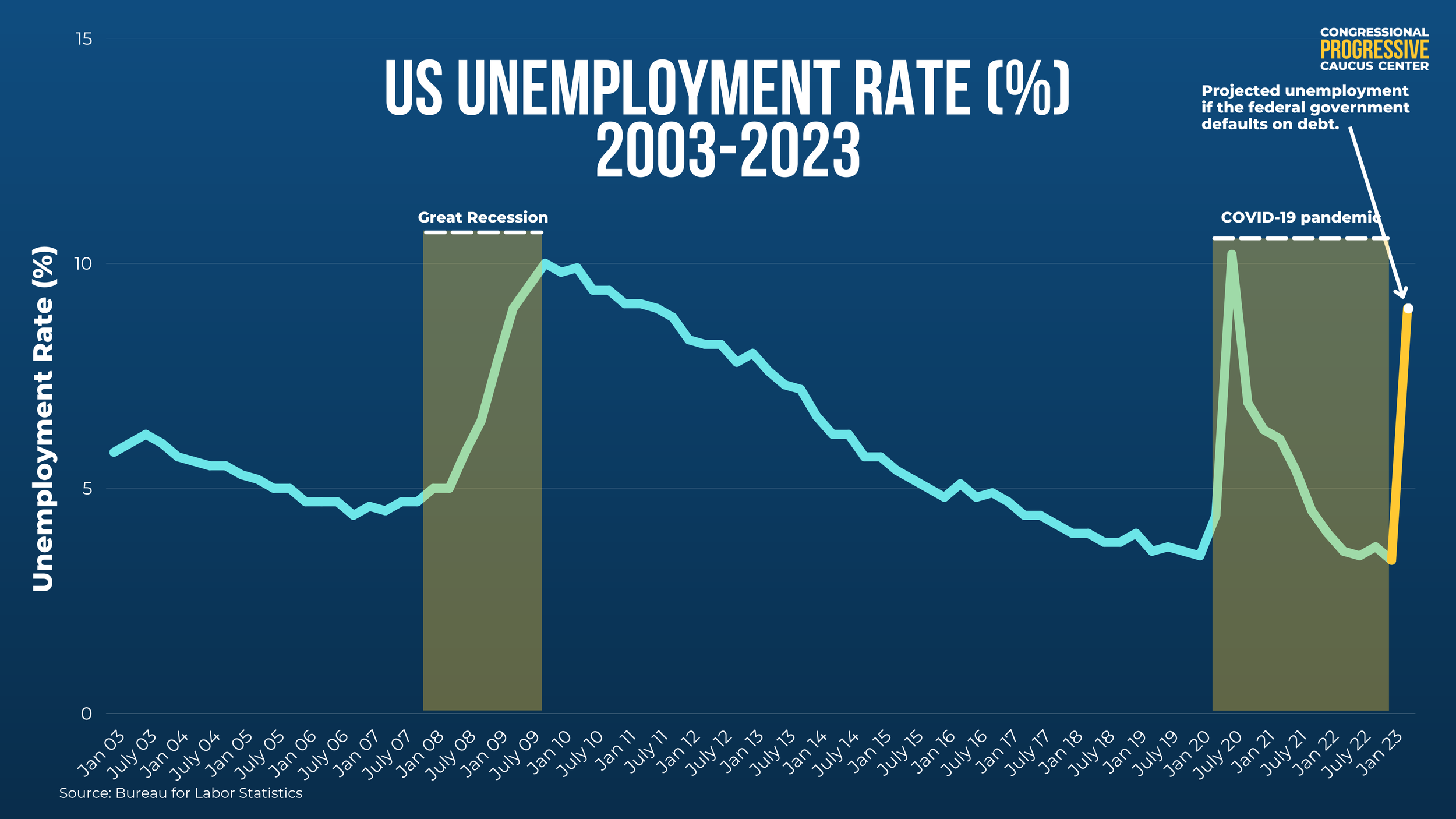

A default could immediately trigger a worldwide financial crisis because the global financial system relies on Treasury securities as a safe asset. It would also do long-term damage by permanently increasing the cost of borrowing for the federal government. This means the U.S. would have to pay more over the long term to provide the same government services that families depend on now. Households nationwide would feel a default’s economic impact. According to an analysis by Moody’s Analytics, a default would force the government to dramatically reduce spending, including delaying billions of dollars in Social Security payments. A debt default could also wipe out $15 trillion of household wealth. The scenario would be comparable to the 2008 financial crisis, resulting in millions of job losses and a spike in unemployment from the current 3.6 percent to 9 percent.

Despite the economic chaos that would ensue, congressional Republicans have used the threat of default as leverage multiple times in the past decade. In 2011, for example, former House Speaker John Boehner insisted that federal spending be cut by one dollar for every dollar increase in the debt limit. President Obama and congressional Democrats ultimately agreed to the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011, which raised the debt limit and capped federal spending for the next decade. In 2013, Congress came within days of debt default amidst a 16-day government shutdown as congressional Republicans pushed for the repeal of the Affordable Care Act. Subsequent debt limit negotiations have been relatively less dramatic. Most were part of budget agreements that relaxed the discretionary spending caps that the BCA of 2011 put in place.

Where Things Stand Today

On March 9, President Biden released his Fiscal Year 2024 budget proposal, which the White House asserts would reduce the federal deficit by about $3 trillion over 10 years. The Freedom Caucus responded with budget proposals to enact enormous spending cuts and overhaul federal policymaking in exchange for preventing default. In addition to the cuts mentioned above that would block student debt relief, green energy and tax enforcement funding and clawback aid that allowed communities to respond to the pandemic, the Freedom Caucus plan could result in hundreds of thousands or millions of Americans losing health coverage through Medicaid.

Also on March 9, House Republicans advanced a legislative proposal that, they claim, would help mitigate the economic fallout should the U.S. default on its debt. Their Default Prevention Act (H.R. 187) would, in the event of default, direct the Treasury to prioritize paying down the nation's existing debt, Social Security and Medicare benefits, and Department of Defense and veterans benefits. The proposal would also prohibit the Treasury from paying the president, vice president, executive appointees, and Members of Congress unless all other financial obligations are met. However, Treasury Secretary Yellen criticized the bill as a debt “default by another name” and urged Congress to maintain the United States’ commitment to pay all of its bills. Moreover, Secretary Yellen noted that prioritizing some payments over others would result in economic chaos and could lead to a credit rating downgrade.

Legislative Options to Raise the Debt Limit

Regular Order

Congress can consider a debt limit increase or suspension on its own or as part of another bill. Under regular order, a debt limit adjustment would require 60 votes to avoid a filibuster in the Senate. Under the Senate’s current makeup in the 118th Congress, nine Republican Senators would have to join all 51 Democratic Senators to end the debate on the bill. The bill itself only takes a simple majority to pass. Alternatively, Senate Republicans could agree to a unanimous consent request for the bill to pass by a simple majority vote. The Senate had used this method before, most recently when they passed a short-term debt limit increase in October 2021.

However, the increase would still need to pass in the House, where Republicans have a four-seat majority. Over the past decade, Congress has gotten creative about adjusting the debt limit through regular order. In 2013, for instance, Congress let the Treasury Department suspend the debt limit but then allowed Members to vote disapproving of that suspension—without actually stopping it. The vote gave Members who have prioritized deficit reduction the chance to save face without threatening a default.

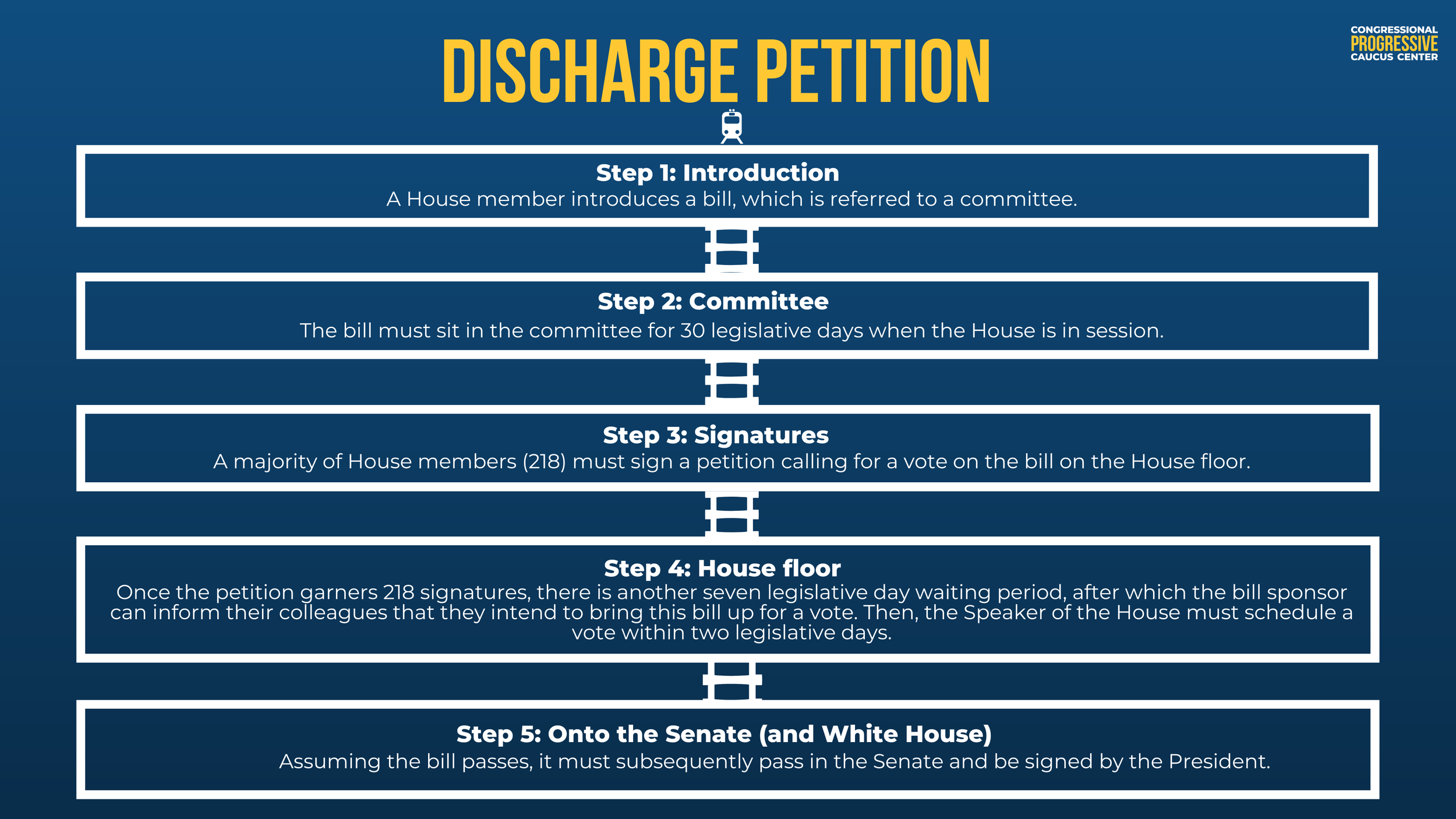

discharge petition

Should House Republican Leadership not call a vote on a debt ceiling increase or suspension, House lawmakers could attempt to force a vote via a discharge petition. The Speaker of the House ordinarily schedules votes on the House floor. A discharge petition is a parliamentary tool that lets members who are not the Speaker force a vote on the House floor if the bill has support from a majority of House members (218 members). While Republicans have more than 218 members in the House, if this process is being used, it is likely because the Speaker does not want this bill to come to the floor. As such, a number of majority party members must publicly act in defiance of their party leader’s wishes for a discharge petition to succeed.

Options for Executive Action

In the extraordinary event that a debt default is imminent, the Administration may pursue executive action. However, these actions have little precedent and could be subject to legal challenges.

Trillion Dollar Coin

If Congress fails to raise or suspend the debt limit, President Biden could hypothetically direct the Department of the Treasury to mint a coin worth $1 trillion (or another large amount), deposit it with the Federal Reserve, and use the funds to keep the government running.

Invoking the 14th Amendment

Section 4 of the 14th Amendment reads: “The validity of the public debt of the United States ... shall not be questioned.” Some legal and constitutional scholars have argued that the debt limit is unconstitutional, as the threat of default questions the government’s public debts’ validity. The Administration could adopt this interpretation, ignore the debt limit, and continue issuing debt. However, the legal uncertainty around this theory could still cause significant economic damage.

Ending the Cycle of Debt Ceiling Crises

While increasing the debt limit to a certain amount or suspending it until a specific date addresses the immediate crisis, it sets up a similar situation whenever the government inevitably reaches the debt ceiling or when the suspension expires. Although Congress has never failed to raise or suspend the debt limit and has protected the full faith and credit of the United States, the government has come close to default too many times. Unfortunately, Congress will continue to put the country in these difficult situations unless debt limit crises are eradicated.

The most obvious way to prevent a future crisis is to eliminate the debt limit altogether, a move that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen supports. Some lawmakers have introduced legislation that would do just that. Rep. Bill Foster (D-IL-11) introduced H.R. 415, the End the Threat of Default Act, which would repeal the debt limit for good. During the 117th Congress, Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA-2) introduced H.R. 1041, To Repeal the Debt Ceiling, which would also repeal the debt limit, and H.R. 5415, the Debt Ceiling Reform Act, which would transfer the duty to raise the debt limit from Congress to the Treasury Department. However, the current House is not likely to advance these bills.

Another way to prevent future threats of default is to raise the debt limit to an amount the Treasury would never conceivably hit. Former House Budget Committee Chairman John Yarmuth (D-KY-3) endorsed raising the debt limit to a “gazillion dollars,” rendering the debt limit effectively inoperative. In addition, enacting a long or even permanent suspension could avoid similar crises years into the future.

Conclusion

For over a decade, the debt ceiling has repeatedly prompted a manufactured crisis and threatened the U.S. economy. Deficit-hawk lawmakers are poised to again use a debt ceiling showdown as leverage to impose austerity measures, similar to the 2011 standoff that resulted in significant cuts to essential programs. Such cuts disproportionately impact vulnerable communities that depend on government services. Families will only be safe from debt limit crises for good when Congress stops manufacturing them. Eliminating the debt ceiling would break the cycle of showdowns and painful compromises, offering families certainty that the services they depend on will not be held hostage.